I do so love it when people make accessibly, entertaining, highly educational science stuff.

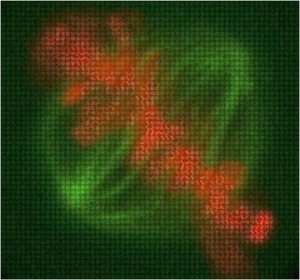

In the latest of such moves, researchers from EMBL and the Mitocheck Consortium (both in Europe) have built up a library of movies showing what happens to a human cell when a particular gene is switched off. One at a time.

This is a vast undertaking. There are some 22,000 genes in the human genome, and the researchers silenced or inactivated each of these, one by one, and filmed what happened to the cell over the next 48 hours. The result? Almost 200,000 time lapse videos, which they then analysed** via an algorithm (developed by them) looking for what goes wrong, and in what order.

But why were they doing this?

The researchers in question want to study mitosis, and the molecular mechanisms behind it. One of the most fundamental cellular processes, it’s the name used for when a cell splits in two: the most common way in which cells replicate (no shagging for them, as it were). In order to study it, however, they needed to figure out which genes are involved in mitosis.

Now, as everyone (hopefully) knows, genes don’t come with handy labels describing their purpose(s). Instead, we figure out what they do by silencing them, and watching what happens. To look for genes specifically involved in mitosis, then, necessitated that the researchers look at all genes initially, and whittle it down from there. Which they did, by having their very clever algorithm looks for genes which, when knocked out, had specific effects such as cells having 2 nuclei instead of the more modest and normal 1.

And, of course, the process they developed allowing them to accurately, and quickly, knock out specific genes is also a very exciting development for the scientific community.

That these genes were actually involved in mitosis was of course then confirmed, but the scientists involved say we’re still a long way from fully understanding the process. Still, this is an exciting development for anyone interested in gene function, whether mitotically-involved or not.

For those interested, the study used HeLa cells, the subject of an excellent book entitled “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” and widely regarded as one of the best popular science books in recent times (if not ever).

The movies, and more information on the data behind the project, can be found here.

———

* Mystified by the term ‘spindle’. Wondering what on earth this strange, globe-like structure means? For a simple primer on how mitosis works, go here.

**Because, of course, that’s a few too many movies for anything other than an army of people to analyse, and who has the budget for armies of postdocs?

Reference:

Neumann, B., Walter, T., Hériché, J., Bulkescher, J., Erfle, H., Conrad, C., Rogers, P., Poser, I., Held, M., Liebel, U., Cetin, C., Sieckmann, F., Pau, G., Kabbe, R., Wünsche, A., Satagopam, V., Schmitz, M., Chapuis, C., Gerlich, D., Schneider, R., Eils, R., Huber, W., Peters, J., Hyman, A., Durbin, R., Pepperkok, R., & Ellenberg, J. (2010). Phenotypic profiling of the human genome by time-lapse microscopy reveals cell division genes Nature, 464 (7289), 721-727 DOI: 10.1038/nature08869