Our brains’ internal representations of ourselves are not, it would appear, quite as accurate as one would have thought.

That, at least, is the conclusion of paper which just came out in the dangerously-acronymed PNAS*.

To introduce the subject, then, let’s agree that it’s important for the brain to know where all our various physical bits are. It stops us walking backwards into things, not accidentally kicking people under the table, and so forth. No doubt you, dear reader, can come up with a wealth of such instances (extreme data overload today precludes my ability to do so).

Oh, and it’s also very useful (perhaps most useful) for our ability to tell where our body parts are in relation to each other.

Further, whereas external sensory stimuli might tell us where bits of us are - aaarg, I know where my face is because I just walked into a door - we don’t generally get the sorts of stimuli which might tell us about the size and shape of said bits. So, our brain needs to resort to internal models it’s built.

One would assume that such internal models are relatively accurate, particularly given that we are often able to see our bits. Or at least bits of our bits. Intuitively, I would have thought that my brain would have assimilated this visual information into its internal models. I’m sure such as assumption is shared by many other people. And you know what?

We’re dead wrong.

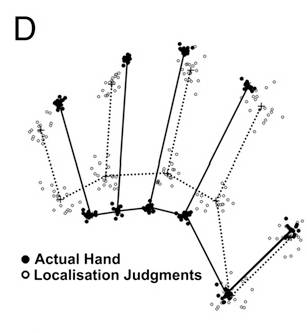

The researchers looked, specifically, at people’s internal representations of their hands. They got people to put their hands under a solid surface and then to point to where they thought the knuckles and tips of each finger were. These pointings-at were then used to build a map of people’s ‘internal’ hands.

And, interestingly, they found that pretty much across the board, people thought that their hands were wider, and their fingers shorter, than was actually the case.

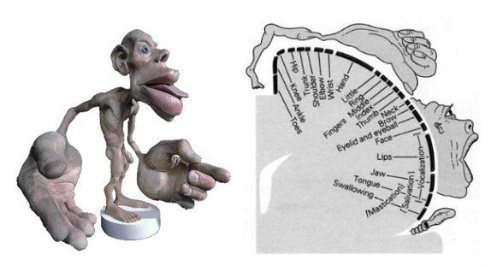

Fascinatingly, this distortion also seems to have something in common with representations such as the Penfield homunculus. What’s that? It’s a representation of the body where the size of the body part is in proportion with the number of connections between the brain and that bit. Which makes for a very scary picture, but a very interesting way of immediately understanding how we’re wired up. This paper suggests that the homunculus may provide not only a picture of our wiring, but also a picture (at least to some degree) of what our internal map looks like.

Ok, so given this, how is it we’re able to have such fine manual motor control? The authors put forward a couple of different possible hypotheses: maybe the motor system just thinks about the end point, not bothering much with the limb’s representation. Or, maybe the motor system uses a different representational model of the body, perhaps by integrating visual inputs. We’re not yet sure, basically.

I feel I do need to emphasize, though, that this distortion is in our mental model of our bodies. In other words, our conscious body image of ourselves tends to be pretty accurate - it’s the internal model that’s not. On the other hand, it might help explain why some people (anorexics, for example) have such skewed body images - their mental map has performed some sort of coup and displaced their body image…

Certainly it’s all very interesting. And it comes with a new word, for all the linguaphiles out there: proprioception. Or, the ability to know where your bits are without having to look.

For a fun game, go home, blindfold yourself (or a close friend), and see how accurate you can be :)

———————-

* Warning: Be very careful when saying this acronym. I have not always been, to much hilarity/embarrassment.

Reference:

Matthew R. Longo and Patrick Haggard (2010). An implicit body representation underlying human position sense Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences : 10.1073/pnas.1003483107

Pingback: Distorted Body Perceptions | Aesthetics of Touch()

Pingback: This is your brain on hacks - misc.ience()