Workers! Throw off your shackles! Be not afraid to be seen by your boss cooing over Cute Overload!

Hiroshi Nittono and colleagues, of Hiroshima University in Japan, have shown something most intriguing: that looking at ‘kawaii’ or cute images of baby animals improves focus and careful behaviour.

It is, perhaps, not surprising that the research originated in Japan where, as the researchers say in their paper, “Cute things are popular worldwide. In particular, Japan’s culture accepts and appreciates childishness at the social level”.

Previous research has shown that the faces of babies can elicit care-giving impulses in humans (not surprisingly**), and also suggested that cute images can encourage friendliness. However, these previous studies had not examined whether or not the positive feelings engendered by seeing something cute had a behavioural effect afterwards.

The experiment was conducted in 3 parts, each narrowing down the effect of seeing cute images, and its possible cause.

Experiment 1

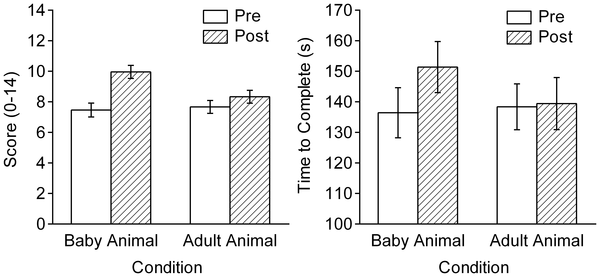

48 college students between 18 and 22 (half female, half male) were asked to play something very like the game ‘Operation’, which tests fine motor control by having players use tweezers to pluck tiny bits of out of a “patient”. After a round, they were asked to look at one of two series of images: baby animals or adult animals (less cute)*. They were then asked to play something very like the game ‘Operation’, which tests fine motor control by having players use tweezers to pluck tiny bits of out of a “patient”.

Upon repeating the game, the people who had looked at the pictures of the baby animals showed improved performance and accuracy, but at a cost: it took them longer to complete the exercise.

According to the paper, this allowed more than one interpretation of the underlying mechanism. The first was that the improved performance could be due to a general slowing-down: it has been previously shown that people speak more slowly and clearly to babies than they do to adults. This slowing-down could then be passed onto any subsequent tasks, and would benefit any tasks requiring accuracy, but impair any requiring speed.

The second possibility was that the effect might not be specific to motor skills. Caring for babies, as the paper says: “not only involves tender treatments but also requires careful attention to the targets’ physical and mental states as well as vigilance against possible threats to the targets”. This would mean that performance in a non-motor, perceptual task would also improve.

Third, it could be caused by an increased interest in social interaction, which would mean that a task would be performed better if it could be seen as benefiting others in some way. On the other hand, a task without any social component wouldn’t be performed better at all.

And hence the second experiment, which was designed to test from amongst these options.

Experiment 2

48 participants (different people from Experiment 1, but again split half female, half male) between the ages of 18 and 20 took part this time.

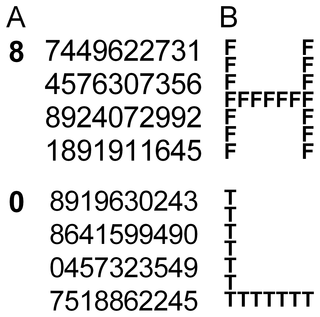

In this, the experimentees were shown sheets on which 10 matrices had been printed. Each matrix showed 40 different, randomly arranged digits, and the participants were then asked to identify how many times a given number occurred in each matrix (a different number per matrix), with answers varying between two and six. In 3 minutes.

Otherwise, the experiment worked pretty much the same as Experiment 1, with one major addition: an additional series of images. Pleasant foods, in fact.

Once again, those who’d seen the baby animal photos outperformed the other groups. Interestingly, while women did far better on this visual search test than the men, the cute images didn’t affect this in any significant way.

The results from experiment 2, then, showed that looking at cute images improved fine motor control. It also showed that it improved carefulness “in the visual domain”. The researchers posited that this improvement in the ability to find a visual target could be because attentional focus was narrowed - attentional focus is the ability to focus on environmental cues which are relevant to the task at hand. Basically, participants were narrowing, and deepening, their attention and focus.

And so on to experiment 3, which was set up to see whether looking at cute images would affect this attentional focus.

Experiment 3

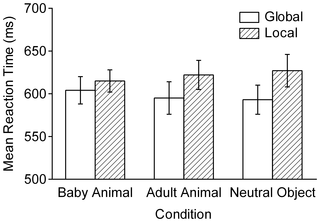

As a general rule, researchers have found that people are better at seeing a ‘global’ than a local picture. For example, looking at a picture made up of other pictures, and finding it easier to see the composite rather than individual pictures.

In this experiment, which again used a 50/50 male/female split of 36 participants aged between 18 and 22, a reaction time test was undertaken.

After viewing either cute baby animal photos, adult photos of ‘neutral’ photos, the reaction time involved participants looking at a letter composed of smaller letters, and seeing whether the letter contained an H or a T. In some cases, the composite letter was an H or a T, and in others, the smaller letters included Hs or Ts. Before seeing the photos, as one would expect, people were better at identifying the global letters - this natural inclination towards the global is called the ‘global precedence effect’.

However, afterwards, those who had seen the cute baby animal photos showed a decrease in this effect - in other words, they became better at focusing on the local, rather than the global.

Participants performed the task in three blocks during which images of baby animals, adult animals, and neutral objects were presented every eight trials (N = 36). The error bars indicate the standard errors of means. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046362.g004

To wrap up

The paper, which is available to download free from PloS ONE (see reference below), then goes into some very interesting discussion about what the underlying mechanisms causing all this could be. It also points out, to its credit, its own limitations - these include the need for a better understanding of the psychological state which underlies the feeling of cuteness, and also the need to look at how different cultures might react to cuteness.

However, what it does show is very clear - that being shown pictures of ‘cute’ things, such as baby animals, and the positive emotions this triggers, improves attentional focus and behavioural carefulness.

Next steps? From the researchers themselves:

For future applications, cute objects may be used as an emotion elicitor to induce careful behavioral tendencies in specific situations, such as driving and office work.

So, there you have it. Back to those kitten pictures, all of you. And if your boss complains, show him this, and explain: it’s good for your work :)

—-

Fun facts: cute and kawaii

From the paper itself (I found this fascinating):

Kawaii is an attributive adjective in modern Japanese and is often translated into English as ‘‘cute.’’ However, this word was originally an affective adjective derived from an ancient word, kawa-hayu-shi, which literally means face (kawa)- flushing (hayu-shi). The original meaning of ‘‘ashamed, can’t bear to see, feel pity’’ was changed to ‘‘can’t leave someone alone, care for’’ [4]. In the present paper, we call this affective feeling, typically elicited by babies, infants, and young animals, cute.

—-

Reference

Nittono H, Fukushima M, Yano A, Moriya H (2012). The Power of Kawaii: Viewing Cute Images Promotes a Careful Behavior and Narrows Attentional Focus PLoS ONE : 10.1371/journal.pone.0046362

—-

* In separate tasks, participants were asked to rate how cute the pictures being shown them were, so that the researchers could be sure that, for example, the cute pictures of the baby animals were, in fact, cuter than of the adult animals.

** I remember reading somewhere, years ago, a paper suggesting that humans and dogs had co-evolved, with dogs using our penchant for the cute (PUPPIES!!!) as a means of, well, domesticating us. It has a certain something to it, I think :)